A follow on post to the yesterday’s post on Alba II, here’s the minor houses of that world. Cailean is the family that my players have been running for their game; the Mazzola were their main rival for the first “book”.

HOUSE CAILEAN

House Minor, vassals to House Fujimori.

Traits: Loyal, Meritocratic

House Crest: A boar’s head on tartan (blue and green primary, white and yellow striping).

House Motto: Never Forget.

Domains: Primary, Farming (Produce); Secondary, Artistic (Produce).

Rivals: House Mazzola — House Minor; reason, ancient feud.

House Reputation: Respected (30)

House Skills: Battle: 5, Communicate: 7, Discipline: 6, Move: 4, Understand: 5

Notable Persons:

- Ruler: Donchard Colm Cailean — head of the Cailean, councillor to Fujimori. (Picturing a Brian Cox,-type)

- Consort: Lady Aline (nee Aristona)

- Heir: Laird Halan Cailean (25 yo and anxious to do something important)

- Other Children: Malcolm Cailean (18 yo son)Bari Cailean (16 yo daughter)Ian Cailean (13 yo son)

- Advisor: Laird Lorne Cailean — head of nascent house/clan, McCailean

- Councilor: Laird Sean McCailean (cousin to Laird Colm)

- Marshal: Marshal Donella Zyrhan

- Swordmaster: Lady Captain Siobhan Cailean — 22yo daughter and Swordmistress of Ginaz

- Treasurer: Donal Baris

- Warmaster: Bator Mak Drummond

Connected Nascent Houses: Calder, Drummond, McCailean, Mohr

Notes on House Cailean:

HOUSE CAILEAN was the first house to settle Alba II several thousand years ago. Much of the early history is half-legend, and even the Imperial Records have little on the first few millennia of Alban history. From the start, a rivalry with House Mazzola was established. Much of this has to do with early claims to the world, but as time has gone on, it is deeply tied to different views on the nature of government and its relationship to the people it governs.

The Cailean view their position as more of a steward of the people, rather than as a ruler. They have traditionally supported the education of their people and allowed for a certain amount of social mobility based on merit that the rigid framework of Faufruchles does not. The Mazzola, highly religious and socially static, view the Cailean attidues as “libertine” and dangerous. As a result, there is les incursion by official religious programming in Cailean lands than many places — one of the reasons for the 75th Padishah Emperor’s move to place the Fujimori over the Cailean and Mazzola on the planet.

They are famed for the Alban beef and stonefish — delicacies throughout the empire, as well as their excellent liquors: whiskies, gin, and ciders. Another point of fame comes from their liberal attitude toward education and expression: Alban, and specifically Cailean, poets, playwrights, and musicians are regular members of House Jongleur.

The peoples of Hyperborea view family as the center of life, and view those not part of the “clan” as something to be watched, if not outright distrusted. For this reason, most senior positions in the Cailean government and military are family, or closely trusted confidants. When a Cailean takes you as a friend or family, it is an unbreakable bond. They view the interfamilial court intrigue of the empire as distasteful and destructive. Cailean is a house with three main clans related to the noble house: the clans of Cailean, Calder, McCailean, and Mohr. There are other people and families related — the Moray and Stewarts — but these are the ones that are nobles. The House is lead by Laird Colm Cailean, or the Donchard and Laird of Ben Cailean & Glenmoran. His heir is Laird Halan Cailean. The Calder are lead by Laird Halan Calder, the Laird of Stanehome. He is a cousin to the main line. Laird Lorne, brother and advisor to Laird Colm, heads the recently created House McCailean, and is now Laird Lorne McCailean of Stainhome.

Their dialect is one of the purest forms of Galach in the Imperium — possibly going all the way back to Earth, itself. While most educated people also speak Nihon, the language of the Fujimori, once out of the cities, Galach is the dominant tongue in the north.

As a result, the Cailean Militia follows this rank structure:

- Bashar — leader or the militia (Laird Colm)

- Subashar — leads a division of militia

- Bator — leads the air group

- Commander — leads an air wing

- Major — leads a regiment

- Captain — leads a company

- Lieutenant — leads a platoon

- Sergeant — leads a squad

- Corporal — leads a team

- Trooper

The Cailean Militia are generally unshielded and wear light armor. Their uniforms are composed of a green, high-necked jacket over kilt in the Cailean tartan. Knee-high boots have a scabbard for the ceremonial dirk. This is topped off with a Glengarry cap and a fly plaid pinned with a Cailean badge in the house colors that is used as a blanket or cloak in the field. Standard equipment is a broadsword and lasgun rifle.

A new unit under Lady Siobhan, the Black Guard, wears the same uniform in black. They use shields and a Fujimori-style tanto.

To police the Cailean lands, the Cailean Constabulary is a separate force that can be used in ground defense situations. Their uniforms are blue, instead of green, and their carry the ceremonial dirk and a slug-thrower sidearm, as most of their encounters are unlikely to involve shielded opponents. The constabulary’s rank structure follows:

- Marshal — military equivalent: bator; leads the Constabulary

- Deputy Marshal — military equivalent: major; runs a city or province

- Chief Inspector — military equiv. captain; leads investigation team

- Detective Inspector — military equiv. lieutenant; leads investigations

- Detective Constable — military equiv. sergeant; conducts investigations

- Constable — basic policing

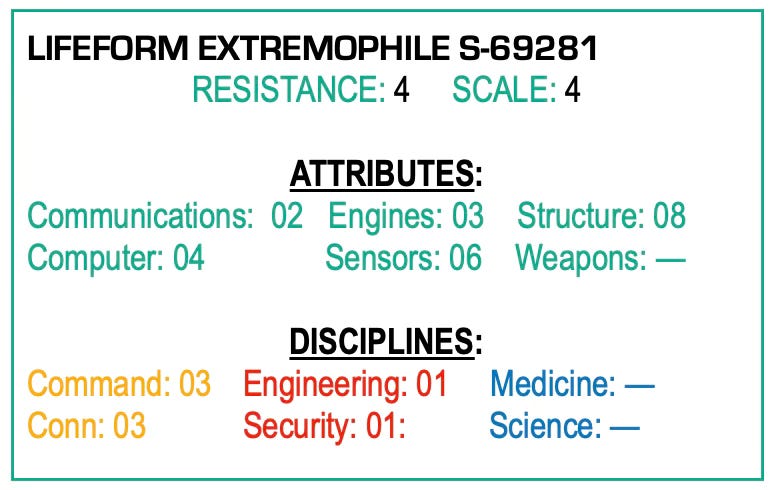

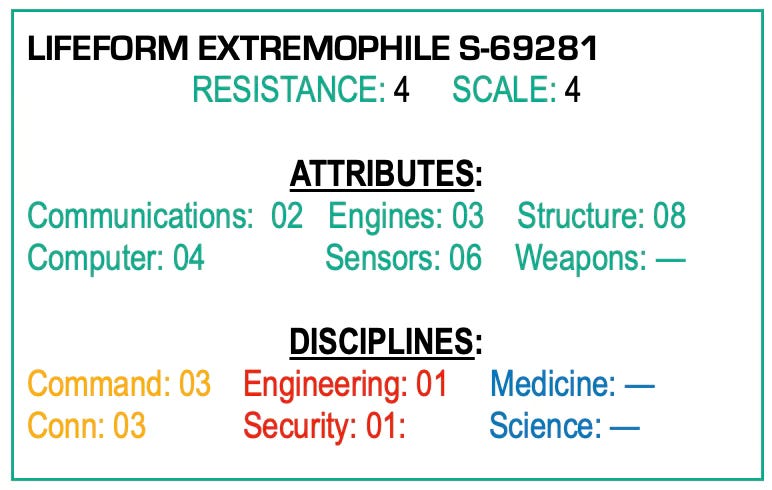

The 2d20 system and Modiphius Logos are copyright Modiphius Entertainment Ltd. 2020. Dune © 2021 Legendary. Dune: Adventures in the Imperium is an officially sub-licensed property from Gale Force Nine, a Battlefront Group Company. All Rights Reserved.

Original material — Alba II and locations, House Cailean, Fujimori, and Mazzola — copyright of Black Campbell Entertainment, but go ahead and use it. That’s what it’s here for. Just give us credit.